THE SNOW WAS still falling outside, blanketing the streets in its deceptive white, coating the walkways with black ice. On the inside, drifting under the rounded blue notes of smoky barroom jazz, muted saxophones remembering other times, the unsense of the world spread out around him like the snow melting away from his pant legs. Dark puddles around his feet.

A man slumped over an ebbing whiskey glass, staring intently, alone. A couple wrapped in the cocooning oblivion of themselves. And from where he sat, nothing fits together anymore. Not like it used to. Not anymore. Outside, the snow flew past. Slush on the streets. On rue Danton and rue Hoche, there on the corner. In a Paris suburb, lost in time. Almost fifteen years from here. Tom was the guy behind the bar. He introduced him to Archie Shepp. Nothing cheerful in that smile.

Just history.

A lot of people wear their history around their necks like a trophy – it complements the successes of today. A good job. Recognition. Appreciation. And behind it all are all the places and times which led here. The glorious path they took. The legendary road leading to a life that adds up to something. He

swirled the bottom of his drink. Maybe one more would be ok. And sure it would – what was the difference? No one wondered where he was. No one to tell him to slow down the flow of the single malt.

His glorious path led him here. And from here, no one was waving him in.

“I just feel like I have done everything before. I have no more wants. Nothing pushes me. This is shit.”

“Nice talk. Now I need the cheering up…”

“I don’t mean to dump on you.”

“Yes, you do.”

“Yes, I do.”

He did. He had to. There was no one else. In fact, there was no one at all since he had just made up this imaginary conversation foil. He had no one to talk to. Tom was gone into the passing years. He might even be dead.

All his life travelling, moving, from place to place. Friends were gone. Some were never there – just placeholders. Now he was inching inexorably towards retirement and what had he accrued? They always want to know what you have accrued. Money? No. Property? No. Accomplishments? Nothing visible. Work?

Being without a real job now for quite some time, he had forgotten what it was like and found the idea of retirement a twisted irony. Sometimes the idea of once again getting up and going to some nondescript office and performing repetitive and meaningless tasks seemed like the ultimate thing

that would restore some kind of order to his life. But he also knew that he could not do that for long. His was the gift of ontology, allowing him to strip away the unreal and the senseless. But once they were gone, he found he could no longer stand to be part of it anymore. A gift. Where being, becoming, existence, and reality could not hold his attention.

To look onto pointlessness and strive on. He never could. He can’t now.

2.

EVERY MONDAY MORNING, someone had to bring the donuts.

They took turns around the office, but everyone loved it when Margery’s day came around. She made them herself. They were the perfect sugary tonic to offset the bitter taste of a Monday morning in a gray cubicle in an office space without windows.

Glazed, vanilla, jelly-filled Bismarcks, bear-claws, elegantly frosted, light and airy for some, cakey and substantial for others. Margery is the best. Everyone agreed.

They worked in a factory excrescence. The Dinglemacher family had invented a process for dicing meat bi-products and packaging them as salad supplements (fixin’s some called them) or including them in sandwich spreads. The DG3400 Industrial Meat Dicer-Packager was patented nearly 60 years ago in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and was still standard in many meatpacking plants throughout the Midwest. Rath meatpackers and Iowa Premium had both penned testimonials that had been hanging on Mr. Werner Dinglemacher’s office wall since 1969.

The factory was built here on the west bank of Black Walnut River. As Dinglemacher Machines began to grow in size and stature, the early management needed more room for more people. They expanded the sides of the factory with concrete floors, corrugated tin roofing, and aluminum siding until it looked like the original plant was pregnant with triplets. From three sides. The walls and roofing were double insulated, of course, but no one thought about putting windows.

So it was a large box full of small cubicles.

“Not everyone knows, but jelly doughnuts were also called Bismarcks because of the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. Since this region had a lot of immigrants from Germany and central Europe, we started calling the jelly doughnuts Bismarck. Most of the Upper Midwest, parts of Canada, and even in Boston too,” Brad Miller confided, a sprinkle of powdered sugar clung to the bottom right of his beard. He had told this story before and most of the factory had it memorized.

“Is that right? Boston, Massachusetts,” Horatio Stephens distractedly confirmed his listening even though he continued to peruse his open newspaper. Stephens liked Brad well enough, despite his tendency to fill in the blank space with conversational reruns. He was otherwise sharp and quick witted, when properly engaged. At the moment, Stephens had his eye on Travel & Leisure, page 54, and he had not given his full attention to the Bismarck story.

“C’mon Horton, everyone’s heard about that!” Brad drifted off toward his cubicle, trailing sugar dust.

Stephens had been nominally Head of Corporate Communications at Dinglemacher for the past 22 months. It was qualified as nominally because Dinglemacher steadfastly refused to communicate

anything to anyone about anything. The products had a niche in industry where all the buyers knew them. Dinglemacher was the first to come out with that particular kind of dicer and therefore was a renowned innovator among meatpackers.

As Head of Communications, Stephens was listed as a company director. But he had no staff to direct. He shared an assistant, Sally Edwards, with sales, meaning that he had no assistant either. Sales and Production. Those departments were the bulwark and soul of the company. We make ‘em, and you sell ‘em, or so the motto went. Flip-flopped in the sales department.

The rest of us ate donuts.

Today this would all change. Today the status quo in this engineering-led legend was about to take a kick in the teeth. No one knew it yet, but Stephens had been planning this for quite some time. It was a stratagem that was sure to get a result.

3.

HORATIO LIVED THREE miles away from the office and, in the summers, he enjoyed the walk. A stand of white oak, enough to be called a small wood, fenced off the industrial eyesore of Dinglemacher from the town center, making the whole walk take about an hour or so.

Most of the time he drove his finicky second-hand Ford and parked in a place to the left of the front entrance that was designated for him as a director. The Dinglemachers drove Cadillacs, of course. The classic 1959, Coup de Ville sometimes drew curious tourists, just to get a look at it. It was Werner Dinglemacher’s first car.

The irony that this unloved and unsightly industrial pollutant supported and gave life to the whole town weighed so heavily on Horatio as to make his bones creak. Look at him, he thought. He had all the perks of an important-sounding title, working for the town’s single biggest employer. People actually looked up to him saying, “I always knew Horatio would make it.” Horatio didn’t always know it.

He had been working here now for nearly ten years. He started, like most kids from Dyrehaven, as a kid in the warehouse. The last summers of high school were a cut-throat competition for jobs at the plant or jobs in the field de-tasseling corn. Both were well-paid for teenager labor, but everyone knew that if you got into the factory, you had a good chance of landing a better job with Dinglemacher after graduation.

Horatio lugged trolleys and worked forklifts, lifted boxes and loaded palettes between his sophomore and junior years and again between his junior and senior years. Even if he was only 17, the warehouse boss put him in charge of the other summer hires. He saw something in Horatio Stephens that he trusted.

So many had followed this same worn path: from home to school to Dinglemacher and all the way through to retirement with a top-of-the-line Timex and a card that everyone signed. Everyone you grew up with, everyone you were in school with. Your whole life circumscribed and delineated within ten square-miles.

Brad Miller’s family had a nice size farm outside of town, on the opposing bank of the Black Walnut. Horatio had been there many times when he was growing up. He remembered the family dinners around the table, the big drooling St. Bernard (named Bernie, naturally). The evenings hanging out in the living room watching TV. A few times, if he stayed the night, he would help Brad with his chores on Saturday mornings.

Feeding the chickens always mesmerized Horatio. He tossed a handful of pellets and watched the new information spread among the chickens. As if someone said: “Oh? Chicken feed? Yes, I believe I’ve had that before….”

Some of the pellets hit the birds on the heads, whereupon they inspected and pecked them right away, but the rest of the flock watched on a little before slowly joining in. You could imagine them purposely acting casually about it, but then reluctantly succumbing to peer pressure and joining in. Once everyone was in, though, it was a free-for-all: savage, selfish, and unrelenting.

One chicken apparently did not get the memo. She was on the other side of the yard, scratching in the dirt. Horatio threw some pellets her way. She looked up. A moment of understanding passed between them. Then she pecked hungrily at the food.

“Let’s go in now, Huckleberry,” Brad called to him. It is possible that Brad Miller did not even know the name “Horatio”. He was Horton and Harry and Huckleberry, but most often it was Stephens. We called each other by the last name back then. It was way cool.

Brad could not wait to get off the farm and work at the factory. He had pictures of Dinglemacher Machines, ripped from their old corporate calendars, on his walls.

“I’ll be a mechanic,” he told Horatio. “I will keep the machines humming. They won’t be able to do anything without me. What’ll you do?”

“Doesn’t your dad want you to stay here? On the farm?”

“My whole life I wanted to be a Dinglemacher guy, Stephens! You knew that. My dad knows it. My brothers can stay here and butcher pigs.” His whole life, at the time of this conversation, added up to thirteen years.

Horatio listened and wondered. He never wanted to be in the factory. He didn’t know what he wanted to do. His parents ran a busy grocery store on Main Street, near the St. Francis Xavier Church. They started it before Horatio was born and never thought of doing anything else. The one thing that they wanted more than anything, at least according to Horatio’s understanding of things, was that he should finish at the top of his class and go to college. College meant moving away for a while. Ames, Iowa City, maybe to Chicago. It was too much to think about.

“I don’t know. What job do I need to boss you around, Miller?” Brad laughed and punched him in the arm.

Inevitably, Brad Miller ended up working “for” Horatio during their last summer in high school. He recommended Brad for an entry-level job after graduating. But Horatio Stephens would not be there to share in the glory of Brad’s getting everything he ever dreamed of.

In the fall of that year, he moved to Rockford, Illinois.

A degree in business administration qualified Horatio to do everything and nothing. By the time he graduated early, after only three years since that was the extent of his scholarship, Horatio returned home to look for a job, look for a house, and look for the reason for doing either of these things.

During his time at Rockwell, he had drunk too much, met and dated a girl for a year until she left for Los Angeles and her fiancé. He spent much of his time studying in the dorm or in the library or in the

“Bar Expresso” near campus. He tried to convince them that it should be “Espresso”, but they brushed him off good-naturedly every time. They thought it sounded like someone lisping.

Rather than open his eyes to a wider world, Rockford seemed to have the opposite effect on Horatio. He narrowed his focus until, near the end, it encompassed only the width of his open textbook. Everything he learned about business seemed somehow familiar, somehow already seen and done. He developed a sense of disenchantment and the desperate ineluctability of returning home and applying this newly acquired store of knowledge for the exaltation of Dinglemacher Machines.

His degree would earn him a better job. A higher paying job with more responsibility, that was clear. But what he had done was exactly what the rest of the children of Hamlin had done before. With a gap of three years, he joined the line of dancing souls toward the fulfilment of the Apocatastasis of Dyrehaven.

That Dinglemacher will save them all.

His parents were of course overjoyed that he started with Dinglemacher as a senior business development manager. Their pride shone with every mention of his name at the till, in the cereal aisle, in the church basement, and in the barber shop or beauty salon. Their son had become better than the rest of them. Better while staying the same. This was the key.

Horatio listened in astonishment as his father explained it carefully to Mr. Judson after packing his brown paper bag.

“This town is built on Progress, Mr. Judson,” he began, handing the bag across but not quite releasing it. “Each generation builds on the successes of the last. The Fairchilds have the highest corn yields in three counties today. But when we were growing up, they barely had enough to feed themselves. Not dirt farmers, not anymore. It’s Progress.”

Mr. Judson smiled soberly in agreement, hoping acquiescence would free his groceries from the proud father’s grip.

“And our young Horatio – well!” he beamed, warming up to his subject. “We couldn’t be happier that he already has an important position in Dinglemacher. I never wanted to see him here, stocking shelves, thinking about an expansion or a new loading dock in the back. His mother and I saw to that.

“Horatio’s classmates almost all left school and went to work at the plant. They all started at the bottom and are moving up at their own pace. Horatio jumped over them. He has a BBA from Rockford. He knows what the plant will need and how to do it.

“He followed,” concluded Horatio’s father, “by leaping ahead. That’s the beauty of it.”

In an odd way, Horatio had always understood that congratulatory convolution. A fragile filament stretched from bettering oneself, as Horatio had done by going to Rockford, to conforming, which had been accomplished by Horatio’s return.

4.

“I HAD AN idea.”

Brad, feeling the hard thwack of the cudgel upside his head, tripped and turned his ankle under a rolling file cabinet when he first heard the plan outlined for him. Horatio could not keep it to himself anymore, and Brad Miller was by way of being Horatio’s best friend.

“It’s simple but it will not be easy,” Horatio helped Brad into a chair and ran down to and back from the kitchen for some ice, applying it to the reddened ankle.

“We are going to take over Dinglemacher Machines.”

This suddenly became a complex event for poor Brad Miller. He couldn’t determine whether Stephen was joking, crazy, serious, or if he were having some kind of word salad episode. Each of the possibilities molded his expression and articulated itself across his face, like a parade passing solemnly along Main Street. Horatio watched from the sidelines, giving his friend a chance to come to grips with his idea.

“I guess that means,” Brad quipped sheepishly, “you weren’t thinking about rejiggering the lineup for our bowling team” His ankle hurt. His brain was breaking. What in the name of God, Stephens???

Starting from the beginning, Horatio laid out why he had been thinking of options for himself in the company. Nothing he ever proposed for communications was ever accepted. He continued to make proposals for PR events, community outreach, or social media accounts, and each was rebuffed. Social media had been rebuffed with extreme prejudice, including a flight of paper and a stapler being flung at Horatio.

The Internet scared the Dinglemachers.

He had been in this job almost two years and had nothing to show for it. Before, when he was managing supplier relations, at least he could say that he was appreciated, that he could get a few things done. He had successfully wrangled the Iowa Pork Producers Association into an agreement to allow the Dinglemachers a permanent listing as a reference meatpacker supplier. And everyone knew that no one gets anything out of Iowa Pork.

He had sourced machine parts from Germany and France, places so far afield that they would not scatter the pigeons at home by their movements. He had gotten an engraved plaque in City Hall to commemorate the groundbreaking for the plant, and he even connived to get Werner Dinglemacher named to the town council without his ever coming to any meetings.

When they “promoted” him to Head of Corporate Communications, Horatio swelled with the pride of accomplishment. Look what he had done for these people. His just reward had been granted. But slowly the truth began to leak out the sides of his corporate goodie basket. The truth that Horatio Stephens had overstepped and irked his masters. They chose to promote im out of the way. They had ascended him up to Corporate Secret Keeping.

He was being hung in cold storage on one of their own patented meat hooks.

“They don’t like showy,” Brad agreed sadly. “They figured you were gunning for their offices on the second floor. You always do more than they want, Harry.”

The second floor of the factory had always been the Dinglemacher’s private domain. They had their offices there, a full bar and lounge, a billiard room. No outsider had ever been up there. Milton Dinglemacher, Werner’s father, had an “Interview Room” built on the factory floor for the sole purpose of meeting with management and labor. Horatio had used it more than once for meetings, but its real purpose was to serve as a halfway point between the Family above and the Flock below.

As munificently as the Dinglemachers spread the wealth in Dyrehaven, as important as the factory was to the town for income and jobs, they never really cared much about any of it. The Dinglemachers came to Eastern Iowa in the late 1970s from Wisconsin, bringing their pork processing know-how with them. They set up here because of the rivers and the proximity of many local farmers. It was a good idea, but no effort was ever made to fit in. Not really.

“That’s how they govern us,” Horatio declaimed. “They have controlled and manipulated me since the first day, even before college. They make their decisions from their cloisters above and the rest of us hasten to obey.” Horatio stood up to declare this.

“I’ve had enough of it!”

He raised his voice slightly while lowering the register. An oratory trick he had seen once. It worked on Brad Miller. He had been skeptical at first but now was all in.

In that frozen moment, Horatio standing resolutely and Brad shifting forward on the chair, back straight, and ready for whatever was to come next, the decision had been made. The next moves would prove not to be physically challenging; no angry villagers or king’s cavalry would hunt them down and land them in a public pillory (or worse). What Horatio Stephens showed Brad that night consisted of an extreme test of their force of will and sang-froid.

About six weeks earlier as he was poking around the archives, Horatio had stumbled across sketches and diagrams of a piece of gearing that had been integrated into the DG3400 Industrial Meat Dicer Packager.

The device had been invented by the French company Plessis Ingénierie, from the Breton family of Plessis-Mauron de Grenet. A spiral bevel gear set, used to regulate the flow of raw material along the conveyor in parallel with the speed and force of the dicing grill, the French device had never been used in the US up until then. The Dinglemachers must have discovered it by some means and brought it home.

In industrial applications, spiral bevel gears are integral components of many machines. They often get built into milling machines to help achieve precise, controlled movement. Additionally, spiral bevel gears are used in conveyor systems, power plants, and food processing where power needs to be transmitted at right angles.

This is where the DG3400 might have been scrapped even before leaving the drafting room. The processor was working fine, but the gearing systems originally installed by the Dinglemacher’s lacked any kind of precision or consistent movement. The product came out all right, but it was erratic and choppy, not the uniform standardized form to which Dinglemacher aspired.

The Plessis gear set solved everything for the Dinglemacher machine, but rather than get a license, agents working for them managed to get ahold of the specs and smuggle them out of the country.

Horatio smiled when he thought how many French francs had to change hands for that bit of showmanship to transpire, but the truth was an even more exquisite irony.

The Plessis gear set was patented in 1982 in the EEC. During the transition years from the European Economic Community to the European Union, all of the institutions had to make sure their documents passed to the new entity. When the European Patent Office adapted to the needs of the fledgling EU in 1992, the Plessis patent had missed the boat and remained in force only in the countries of the former EEC. Somehow the company’s lawyers let the mistake slide by, leaving Plessis exposed.

Horatio spotted the hidden treasure while poring over the Plessis company information in the archive room. And he wasted no time to act.

He managed to file for and register the Spiral Bevel Gear Set for North American use under his own name, as the Stephens Meat Processing Method. This means that he, Horatio Stephens, owned the US rights to use the gear set and could now extort and wrench control of Dinglemacher from their grubby hands. The process took about 12 minutes and a credit card number.

“How you like THEM apples?”

5.

The interview last for about 20 minutes. The drive home with a box of personals took four minutes. And within the next 48 hours, Horatio Stephens perched uncomfortably in his economy seat on Air France flight 3577, landing at Paris Charles-de-Gaulle at around nine in the morning.

The interview had not gone as planned.

After laying the whole thing in front of Brad, Horatio stepped back and waited. He had thought the whole process out from beginning to end. He would present his position to the Dinglemachers: that they could either relinquish control of the company forthwith or suffer the humiliation of a media drenched court battle. In either case, Horatio had the cards and would end up winning in the end. The license for the gear system was his now and he would be fully within his rights to deny their use of it AND sue them for illegally obtaining it in the first place. He anticipated a glowing reception from his friend and was eager to get to work.

Brad was silent, eyes wide. Part of him tried to work out the logic of the plan, and the other part trembled violently in abject fear for his future. Brad had been working here since high school and did not know anything else. What if Stephens pulled this off? Would he lose his job? Would everyone?

“You would actually do this? Huckleberry? Is this for real?”

“For real.”

“And what happens when it doesn’t work?”

“It’s going to work, Brad,” Horatio went back into sales mode again. “The factory is based on the DG3400, and the DG3400 depends on the Plessis gear set. The Dinglemachers have made enough money to step away from this and do something else. Or retire back in Wisconsin or wherever they are from.

“They are the most private people anyone has ever seen. Public exposure of such a scandal would kill them.”

They went back and forth for what seemed liked hours. Brad could not imagine that these people would possibly give everything up to save their reputations. It was too big a leap. Brad knew that Horatio was about to overplay a hand that was not nearly as strong as he hoped.

Horatio could only think of the upside. He would finally be vindicated after all these years of pointless work, these Sisyphean labors. But mostly, Horatio felt like the Dinglemachers owed him time. He had dedicated himself to the company, to doing the best he could for them, to advancing their business interests, and in the end had nothing to show for it.

The Dinglemachers could not shoulder the whole blame. Since his promotion into the Void, Horatio had come to see the entire system as being pointless. He needed to get out of it fully. Maybe he could start his own company, doing something. Something, no matter what it was, for yourself could only be better than doing the bidding of the world’s Dinglemacher contingent.

Having leverage now, Horatio now raised his head. He saw light and a future, even if the images from that future hadn’t come into focus. He would bring his friend Brad with him, even if Brad currently wore a disturbingly horrified mask of doubt and disbelief.

Werner Dinglemacher, intrigued by Horatio Stephens and his urgent demand for a meeting, took the uncharacteristic step of inviting the young man to the sanctum sanctorum on the second floor.

Crossing the threshold, Horatio perceived that his adversaries were heavily armed and ready for any challenges. The outside of the door was just grey sheet metal with a rudimentary handle. But pulling it open revealed a lush interior. The anteroom was furnished in tasteful mahogany and Ethan Allen. The paintings on the walls were good reproductions of Bruegel or Hieronymus Bosch. Could they be originals?

Werner Dinglemacher appeared in the door to his office, facing the entryway, and beckoned him in. Dinglemacher crossed behind his imposing desk, clear of clutter or objects, and gestured for Horatio to have a seat. Horatio stayed standing.

Brad Miller had been right, of course.

Within minutes of Horatio’s throwing down the gauntlet of indisputable logic and consequence, Werner Dinglemacher gave him what seemed to Horatio to be the deepest look of mournful disappointment he had ever seen. He sighed and picked up the phone.

“Evans? Ask Edna to prepare Horatio Stephens’s dismissal papers, severance allowance, and last paycheck? He will be down to pick them up in a few minutes,” Dinglemacher hung up the phone and looked Horatio in the eye. He held him there in silence for what seemed like an eternity. Until Horatio broke it.

“So instead of discussing this like an adult, trying to reach a mutual accommodation that will save your reputations, you are just going to fire me?”

“Yes.”

6.

NO ONE HAD heard much from Horatio Stephens since that day, fourteen years ago, when he made his final procession along the corridor between the cubicles, a cardboard oatmeal box of personal effects under one arm, and out the door of Dinglemacher Machines. Forever.

Now, shifting himself out of a taxi near his rented rooms in Issy-les-Moulineaux, rue Gabriel Péri, Brad wished he had kept more in touch. He also wished he had chosen a place nearer to the city center.

His street, on the southern periphery of Paris, not far from the Plessis offices, took its name from a journalist, a communist, martyred for the cause of the French Resistance in 1941. Paul Eluard wrote a poem about him. It was fitting.

Plessis was now a wholly own subsidiary of Dinglemacher Machines.

Although a little rounder in the jowls, a little slower in the step, Brad Miller had not changed all that much in the intervening years. Horatio would surely recognize him. Brad still worked for the Dinglemachers, where he had been promoted to the position of Chief of Operations and Logistics. He had earned it, putting in long hours, studying supply-chain theory at night at the library, and listening to podcasts and webinars on the subject.

He wanted it for himself, but also for Marcy and the girls. Marcy worked in order processing, and the two had begun to notice each other very early on during the time of restructuring, just after Horatio Stephens left. After a fairly short courtship, Brad and Marcy were married and now had two girls, six and eight, in school at Herbert Hoover Elementary in Dyrehaven.

Caroline and Hallie.

With his new position, Brad could save for the girls futures and maybe even think about moving into a bigger place. Brad liked the idea of a small-scale farm. The Dinglemachers remained as aloof and distant as they had ever been, but they turned more to the senior staff and made sure to be alert to anyone who might have felt disgruntled.

Horatio Stephens had startled them when he barged in threatening to blackmail them. Sadly for him, the Dinglemachers had bought and paid for the famous gearing set a long time before Stephens got his nose and his dreams into a box of outdated papers.

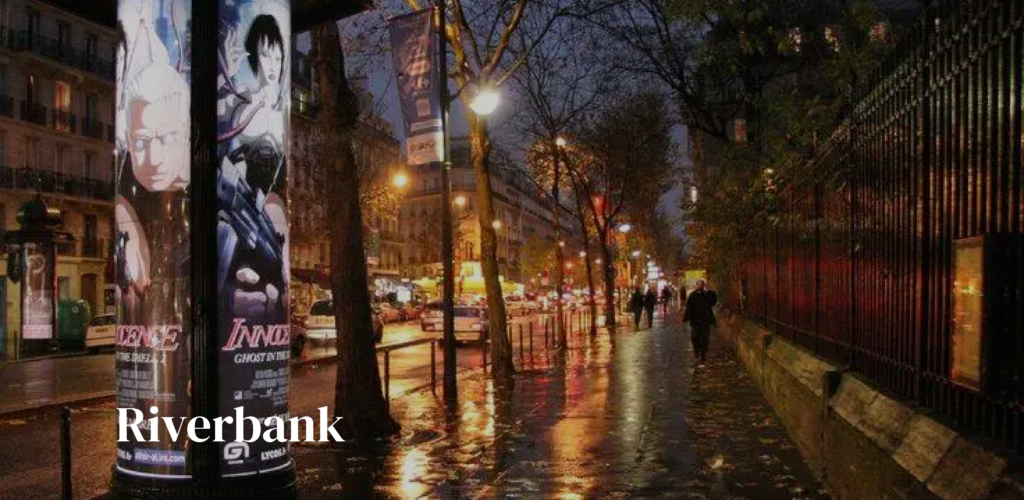

Le Chanticleer, the bar where Horatio agreed to meet Brad on his trip to Paris, was already dark at three in the afternoon. There was smoke lingering in the air despite the ban on smoking in force. The owners of the Chanticleer did things as they wanted. A rich saxophone jazz playlist filled in the spaces and empty barstools with its sorrowful notes. Brad felt like he stepped back in history as soon as the door swung closed behind him.

Horatio got up from where he sat at the bar. He walked slowly over to Brad Miller, his old friend, and threw his arms around him.

“I’m doing some freelance work now,” Horatio explained. “I applied to Plessis when I got here. They told me about their selling the gear, and they did not really have anything for me to do. I have done this and that, enough to allow me to stay in Paris. No one telling me what to do.”

Brad showed him the family, his new office, and a few pictures from their vacation in Colorado last year. Horatio looked on, eyes glazing, as though he were shifting slowly out of phase. He smiled at Brad. The one who stayed behind. The one who stuck with it.

“You were right,” he sighed.